For Starters #10: The Three Risks of Entrepreneurship

"If you graduate Stanford at 22 and Google recruits you....They’ll pay well. It’s relaxing. But what they are actually doing is paying you to accept a much lower intellectual growth rate...Things are cushy where you are. You get complacent and stall." - Stephen Cohen, https://blakemasters.tumblr.com/post/21437840885/peter-thiels-cs183-startup-class-5-notes-essay

At some point, around the turn of the century, I read 'Who Moved My Cheese' ( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Who_Moved_My_Cheese%3F ). When I finished it, I was a bit dumbfounded - "Why was this such a significant book? It seemed to be filled with #StuffIAlreadyKnew?"

It wasn't until 2020 when 'How to Be Fine' put the book into historical context ( https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/epilogue-who-moved-my-cheese/id1217948628?i=1000468170276 ) that I finally understood - the book was for my parents' generation. It was to come to terms with the increased velocity of change - digital technology, globalization, M&A - in the professional world.

In between graduating college and this book came out, my first two employers had already gone out of business. Enter the workforce in the 20th Century - it's easy to wonder what the hell is happening in the 21st Century. Entering the workforce in the 21st Century, you didn't know anything different.

These two experiences - and the four employers afterward - underlined that my professional approach needed to be more surfing waves than cultivating bonsai.

Businesses large and small have all the same operational questions. Sure, small firms may not be as complex, may not have have as many options, but they still need to be answered; customer pipeline, pricing, accounting, marketing, sales, product offerings, employee benefits, taxes, cashflow management, insurance, etc, etc.

In larger firms, each item in the above list is a single person if not an entire team. When the goal is to maintain the financial health of a massive enterprise - this kind of specialization and risk-mitigation can be warranted. For a nascent startup, for a solo-preneur or even a co-founder team, all of these answers are much simpler, cheaper, and much lower stakes, and need to be picked up by one of the founders. Even with the simplicity, it's still a lot of things.

It's so much that I've hear people lamenting the comparative stability in W2 corporate employment.

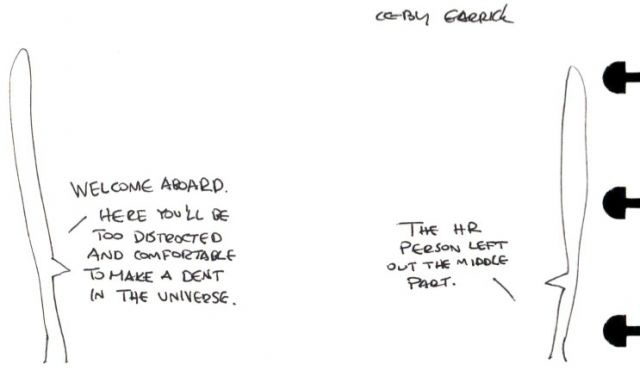

This definition of "stability" means "focus". There's lots of things you don’t need to worry about when you’re a W2 employee:

not enough sales, that a problem for the sales team - not you

not enough profit, thats a problem for the finance team - not you

company healthcare program, that’s a problem for the HR team - not you

garbage overflowing and every surface is sticky, that's a problem for facilities managmenet - not you

you and your team not hitting their deadlines - that’s your problem

Beyond, a sense of focus, I suspect "stability" is a MacGuffin ( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MacGuffin ). We don't actually want stablity - the exact same expectations in exchange for the exact same compensation with the same colleagues year after year afer year. At some point, we'll want something more. We'll want advancement.

"Stability" is trusting your employer is large enough, and likes you well enough, to indefinitely contain your professional and financial advancement ambitions.

The vast majority of businesses in the US are small, not in the "not-massive" definition requried for securing government contracts, but in the human-sized, neighborhood storefront definition of small.

My dentist's office is the size of 72% of all US businesses. ( https://www.naics.com/business-lists/counts-by-company-size/ ):

<5 employees: 12.95M (72% of all US firms)

<10 employees: 1.94M (10% of all US firms)

<20 employees: 0.83M (5% of all US firms)

Total number of firms 50-1,000+ employees: 0.32M

In 87% of US firms, there's unlikely any room for advancement. Is this stability?

And none of this considers the scenario where all the cheese is sold to a PE firm in a strategic rollup.

So, what are the three actual risks of entrepreneurship?

The primary risk in entrepreneurship is consistently securing sales at a level supporting your desired lifestyle: mortgage/rent, utilities, healthcare, vacations, retirement, emergency fund, taxes, kids' college funds, yes — all in (hint: it's probably a B2B professional service).

It doesn't matter if that revenue comes in all at once or as a steady stream dribbled out on a biweekly basis. At the end of the year, it's the same number (though, personally, I find big numbers in bank accounts are always more fun - even for a short while).

The secondary risk in entrepreneurship have is overinvesting relative to sales volume. Provided you avoid overinvesting - and the proliferation of SaaS makes it far easier than 20 years ago - entrepreneurship can be more stable, more rewarding, and a higher intellectual growth rate. Especially with the recent popularity of 'fractional' talent. Not overinvesting means not buying the trappings of a more established organization - this includes hiring employees.

When I first started out on my own, many veteran agency owners warned me about a form of overinvesting dubbed "feeding the beast" - a common and vicious cycle of landing so much work that you needed to hire more people to fulfill it, then needing to continue to land even more work to continue to pay for the people and the overhead, when what you really want is more margin.

Sure, the third risk is burnout. But that's not unique to entrepreneurship, it's a risk anywhere there's such a massive mismatch between expectations, resources, and outcomes that the only way to resolve it is to play a Swedish lawn game ( https://www.amazon.com/Rebuilding-Blocks-Game-Kubb-Together/dp/0986246204/ ).